In our last episode Gordon Hempton narrates his own nature recording story and reveals the best way how to start your trip, how to carefully listen to nature and he talks about his personal impressions, feelings and experiences while he created one of the most extensive nature sound libraries on the planet. His personal nature story is true, near, pure and genuine – don’t miss out to profit from his vast insights.

How to start

Once I arrive, I’ve learned to spend the first evening just relaxing and listening and starting to leave the modern world behind: if I can’t, because of unexpected noise pollution, I will relocate to a nearby, more promising area. I’ve found that the small bones and muscles inside my ear need time to fully relax before I can expect to detect the subtle vibrations and echoes of soundscapes. This resting period also allows any travel induced, temporary hearing threshold shifts to dissipate.

I will get to bed early, soon after sundown, and continue to listen, even in my sleep. Perhaps you, too, will notice a sudden burst of hearing sensitivity at the precise onset of sleep–I believe this phenomenon is the mind handing off the night watch completely to auditory surveillance.

During the night I’ll awaken to the padding approach of a coyote curious about my camp–and surely, every passing jetliner. As early morning comes nigh, any moisture in the air will settle, creating a more humid air layer just above the ground. This more elastic state of the atmosphere will, just before sunrise, push sound propagation to maximum levels. At ground level, my auditory horizon will expand from eight miles to nearly double that in a matter of minutes, but only for a brief while. As soon as the heating action of the rising sun stirs the air, the sounds at the limit of the auditory horizon will begin to come in and out of perception, similar to smoke from a fire stealing the scene from behind it.

A distant coal fired power plant? Time to move at least five miles before I try to listen carefully again. Because the dawn chorus at all habitats is a favorite subject of mine, and because air and land traffic often remain sparse at this early hour, I often seek Quietude by setting up an hour before the day’s first birdsong. Sometimes I set my smart phone to vibrate in the middle of the night. That will rouse me to listen…and possibly setup to record.

How to record

The long wait for the rising sun can be very cold. The insects that trilled the evening before, sustained by the added warmth stored in the rocks, will still be silent. This silence is the canvas on which all sounds will be painted.

On the second day, it’s time to get to work. I will position my microphones by listening through them while I move, paying close attention to my feelings–not my thoughts. Sure, I know intellectually that certain shapes (such as rock parabolas) have special acoustic properties, or certain air layers (such as close to the ground) will allow faster and clearer sound propagation, but these are thoughts, and all I need initially are my feelings. Once I feel that I am near that sweet spot I will begin to circle and rotate my microphones to dial exactly into what feels best and set up there.

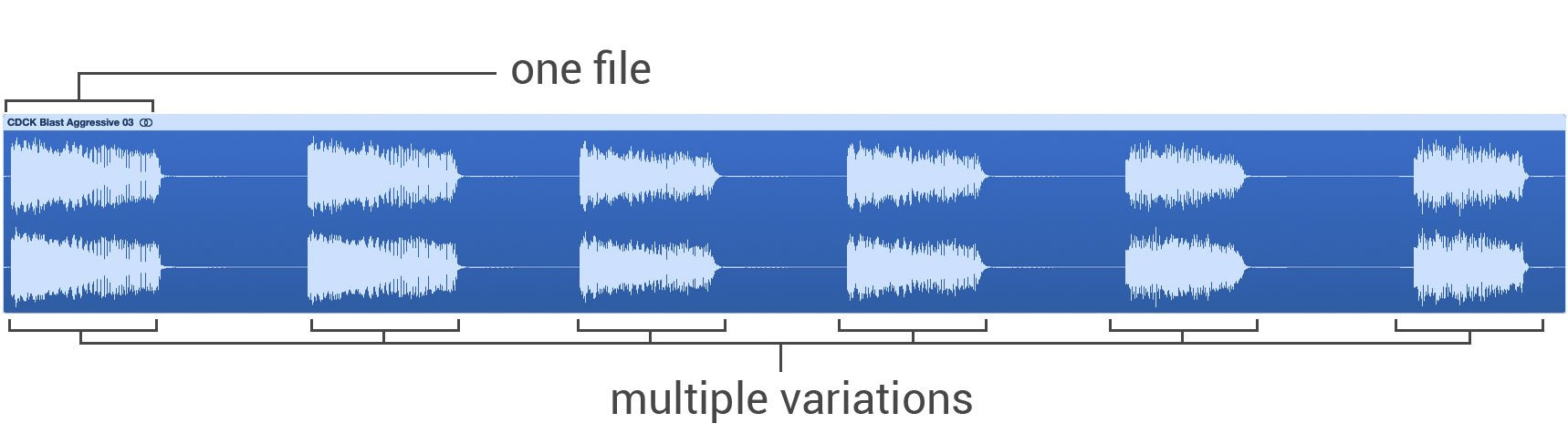

I’ll start recording while I thoughtfully contemplate and examine the portrait currently making its way down the recording chain. I will listen to the faintest sound I can hear and the farthest sound I can hear, usually moving from the distant background to the foreground. I can increase the volume on my headphones (not the gain to the microphones because this could lead to a distortion if a bird sings nearby) to check for the possibility of noise pollution: then having passed this test, reduce the headphone volume back to the intended listening level to conform to the correct equal-loudness contour, which is, in the end, your future audience’s experience.

Now listen again. Do you hear the thrumming sound caused by faint broad spectrum sound passing through the highly repetitive vegetation structure? If not, it could be a rare moment where it is absent, but more likely, you’re unable to hear it yet due to a temporary hearing threshold shift as the result of your travels.

Your microphones will spend the night outside inside a separate drying bag. Microphones kept at ambient temperature perform better. When you start recording in the morning, the cool moist air will not condense on the already cool, dry microphone membrane and circuitry. Water conducts electricity as easily as metal, so by avoiding excessive moisture you avoid possible electronic failure, or worse, very low levels of spurious noise that you don’t detect until you return home and listen more carefully…to your ruined work. The disadvantage of this method is that you must listen in real time to the recording later to determine if your settings were correct. Bring a laptop to load your recordings at the end of each day to learn and make adjustments to your setting the next day.

During a recording you will want to increase the microphone gain to produce a high quality source file. You will also want to adjust the volume on the headphones. Turn the headphone volume up to listen for evidence of noise pollution. Turn the volume down to simulate the real life experience and what your audience might be experiencing.

Listening to my recording now, my eyes have filled with tears as I recall that glorious morning and the revelation of how peaceful a natural place can sound in sustained anticipation of the rising sun. It is the presence of everything. Quiet is profoundly quieting.

Read the nature

If there is a flowering bush nearby, this will no doubt attract birds and insects later in the morning. If there is a dense bush or low tree, it could shelter a sleeping bird that will soon rustle and then begin to sing.

I have learned to watch for signs left by ancient cultures, all but mapping places to listen. I urge you to setup and record wherever you see rock art, petroglyphs, and other evidence of significance. The longer the art took to create the more vulnerable the artist would be, that is, unless it was a special place that collected sounds.

To my ears, the most entertaining sounds occur at the thresholds of human hearing, not just because this is newest information, but by definition, the threshold of human hearing is when the subject of the test guesses more than 50 percent right. This means at the threshold of sound the mind participates in this uncertainty, grasping at answers, and listening imaginatively to this birthing suite of creativity.

Once you have reduced your list to two or three potential recording locations, it is time to call the managing authority for each place and ask to speak with a wildlife biologist. You will first want ask a simple question to warm up the conversation, “Is the area relatively quiet?” The answer may reveal more about the person’s listening skills than the location itself. If the wildlife biologist simply says “Yes,” and does not go on to list sources of periodic noise intrusions, then continue the conversation with your checklist of noise producers (distance to nearest highway, farm activity in area, oil wells, windmills that lift water for wildlife, etc.).

Once I’ve chosen a location I commonly experience the thought: “Nothing is happening.” I’ve learned that this once-disappointing observation is actually great news, and nowadays, quickly set up, then listen through the microphones, invariably discovering, on more careful listening, that noise pollution is present. Transportation sou

nds are generally at fault. Rather than dismiss this location as useless for Quietudes, I remind myself that opportunity still awaits in Noise-Free Intervals.

Trust your feelings

Hear what you hear, feel what you feel. That is how you will do your best work. Whether setting up underwater or on land, do it quickly and intuitively, avoiding critical thoughts at first–just follow your feelings towards your next optimal recording. As you feel, draw your attention to the background first, then move closer. You’ll also want to identify the faintest sound you can hear. Now’s the time to get critical: is it smooth or gritty. If gritty, it could be time for fresh batteries even though your battery indicator shows sufficient voltage.

I dutifully listen not only to the delicate sounds of nature but also the faint evidence of distant noise pollution.

For example, I was recently considering a return visit to Washington’s Pipestone Canyon. This was one of my favorite listening/recording places during the early 80’s when I was first learning the art of field recording. There was one Western Meadowlark in particular that I had come to know over a two-year period by making repeated camping trips from Seattle. I would wake in the morning after sleeping on the ground and setup next to a sagebrush bush where I had watched him and heard him sing his hardest the evening before. The rock wall behind him was highly reflective and the rolling hills that surrounded the Canyon added ripples to his song’s echo. As he rotated his position on the uppermost branch, singing brightly, the reflected sound imaged the constantly changing acoustic environment much like a radar signal reveals land in a fog: quick and bright when facing the cliff walls, then delayed and resounding when facing down Canyon. I’d been thinking of attempting another recording there with some recently purchased equipment. But an up-to-date Google view informs me that a wildfire has recently devastated the area, erasing the concert my remaining lifespan. Thus, I saved myself an unnecessary trip.

It is with this reverence for life that you should silently enter nature’s cathedral, and, if you will, worship—the truest form of listening.

Listen to the pattering of rain, distinctly tapping each leaf, it allows a nice visualization for the audience of the plants close by. The contrast provided by brief drops and long flowing birdsong may also be stunning, especially when the drops progress to include drips.

Listen. Memorize the sound. Take your time—as long as five minutes. Notice that what initially might sound like “just white noise” soon becomes an elaborate braiding of individual streamlets. The more you listen, the more you learn.

Bodysurfing, in fact, has taught me as much about becoming a better listener as sound recording. When riding the waves, I first have to submit to the conditions that exist. Should a mountainous swell suddenly emerge, I simply submerge myself deep into the water. Second, I have to let go of outcome. Will I make a wave behave? Of course not. I can only control my behavior. By getting up to speed with the advancing wave, I can hitch a ride, and then, by feeling the change in the wave’s energy as it drags against the sea bottom, I can change my body posture to fit the wave’s curl, sliding faster and catching a longer ride.

By now, having read carefully the previous chapters you should understand the importance of patience, and listening by placing equal value to all sounds–not just the obvious ones, and should also have learned how to position the microphones with pinpoint accuracy according to your feelings, not your thoughts.

AUDIO DEMO

Feel like reading more of Gordon Hampton’s nature records tips? Check out his book “Earth is a Solar Powered Jukebox” and profit from his experience.

Whether you are a beginner or seasoned veteran, we hope you gained some helpful insights to go out and rock your own nature sound recordings!

Check out the wonderful nature sound libraries (DESERTS, QUIETUDES, CANYONS, WETLANDS, CONIFEROUS-FORESTS, UPWELLINGS, DESIDUOUS-FORESTS, WINDS OF NATURE, TROPICAL-FORESTS, NATURE-ESSENTIALS, FORCES OF NATURE, WAVES, THUNDER&RAIN, FLOWING WATER, PRAIRIES, RIPARIAN ZONES, OCEAN SHORES, HAWAII) including extensive articles about the respective record theme by nature recording genius Gordon Hempton!